It did not come as a complete surprise when, on 1 September 1969, members of the Free Officers movement overthrew the sick, ageing and self-effacing King Idris of Libya, that vast, underpopulated, least known of north African states. Revolutions were very much the fashion in an Arab world still shaking off centuries of direct foreign rule, or indigenous systems installed by foreigners. And, in the wake of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and the blow that shattering defeat dealt to the pride and post-independence pretensions of Arabs everywhere, there had been riots and demonstrations in his otherwise tranquil, western-protected kingdom.

Yet Arabs could expect precious little of what they saw as a uniquely uninspiring land, barren, backward and impoverished – a mere passageway between the civilisations of Egypt and the Maghreb – and could not imagine that it would ever play a decisive role in the affairs of their region, let alone the world, or even aspire to.

They reckoned without the signals officer who led the coup, Captain Muammar al-Gaddafi, who has died aged 69 of wounds sustained when he was captured in his ancestral home of Sirte in the so-far bloodiest uprising of the Arab spring.

Gaddafi was a volcanic child of his times, possessed, from early youth, of a mystical sense of destiny which was enhanced, not diminished, by the very humility of his origins. Born in a bedouin tent, he was a member of the semi-nomadic al-Gadafa clan from the central Libyan coast. He went to a traditional Qur'anic infants' school, about the only form of instruction then available to a boy such as himself, before going on to the Sirte primary school at the age of 10. In 1956 he moved to the secondary school in Sebha, capital of the remote southern province of Fezzan.

It was the year of Suez, the Anglo-French attack on Egypt that marked the emergence of the young Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had overthrown King Farouk and his decadent dynasty four years before, as the Arab champion of modern times. With Nasser as his idol – he too later titled himself colonel – the 14-year-old Gaddafi was caught up in the surging pan-Arab emotions of the time, in the ideals of Arab renaissance, unity, strength and the "liberation" of Palestine.

Expelled from school for his political activities, he continued his secondary education at Misrata, on the coast, and there, with some of his classmates, he decided to join the army as a means of overthrowing the monarchy. In 1963 he enrolled in the Benghazi military academy, where he cultivated his group of would-be revolutionaries with himself as their uncontested chief. After a brief training interval in Britain, he was posted to Khar Yunis, near Benghazi, from where, with remarkable ease, he seized the absolute power which, through many vicissitudes, he managed to preserve until 2011.

Of all such Arab "revolutions", his was perhaps the sharpest, swiftest, cleanest break with the past, the most obviously identified with a single personality. No such leader had more vaulting personal ambitions than he. None, in the shape of a small, easily governable population, and the bonanza of immense oil wealth, should have been better equipped to achieve them. Yet none – even by his own original criteria – was ultimately to fail more abjectly. To be sure, he put his obscure country on the political map. He became a household name, a bogeyman of the western world. But as for the real, enduring achievements of his 42-year career, they were in inverse proportion to the extravagance with which he conducted it.

Nasser was a flawed and tragic idol by the time Gaddafi had acquired the means to emulate him, but an immensely potent one all the same, and had he lived, the disciple would have remained in the shadow of the master. But within a year of Gaddafi's revolution, Nasser had died after a heart attack, and the disciple appointed himself as "leader", "teacher" and "custodian of Arabism" in his place.

The existing Arab order, he preached, was replete with hypocrisy and two-faced policies, with feeble and shameful regimes who worked against, not for, Arab unity and the Palestinian cause in which they claimed to believe. But he would surely succeed where his master had failed. And already he was hinting at yet larger, visionary ambitions than that. "The Libyans," said his second-in-command, Major Abdessalam Jalloud, "are as nothing without Gaddafi … he is neither his own, the Libyans', nor even the Arabs' property, but the property of free men everywhere, from the Philippines to Ireland [the IRA in the 1970s and 80s], Africa to Latin America and Europe."

In this narcissism and self-aggrandisement, he was at least in some measure the child not so much of his Arab times as of the narrow Libyan sphere which he was trying to transcend. In part, at least, they were an outgrowth of something in the Libyans' psyche, a sense of inferiority and an aggrieved conviction that their brother Arabs had never appreciated the immense scale, heroism and sacrifice of their struggle against the Italians before the colonists were driven out by the allies in 1943, in which one-third of the population had died, including many members of Gaddafi's own family. No one believed in his own high destiny like Gaddafi himself. "He who has principles and a mission cannot be restricted by his potentials. When the Prophet Muhammad was given his Islamic mission, he called on the Persian and Roman kings to convert to Islam. Could a bedouin shepherd stand in the face of the Roman and Persian kings?"

His first quest was to unite Libya and Egypt, combining the newfound oil wealth of the former with the large population, skills and education of the latter to make a great state to which other states would rally. In July 1973 thousands of boisterous Gaddafist youths, in buses and cars, streamed across the Egyptian frontier demanding instant merger in petitions signed in blood. It was one of at least half a dozen such unionist experiments, with a variety of partners, which foundered on the rocks of the would-be partners' infirmity of purpose, fear, suspicion and disdain of this bizarre, arrogant, impetuous upstart.

Gaddafi's pan-Arab ambitions were always closest to his visionary's heart. But, frustrated on every front, he began to look inwards, confining himself to the only arena, Libya itself, where his absolute writ ran incontestably. The long-suffering Libyan people became the only possible laboratory for his weird, utopian conceits.

In 1977 he turned Libya into the Great Jamahiriyah. In line with his Third Universal Theory, his answer to the discredited systems of capitalism and communism, the Jamahiriyah, or State of the Masses, supplanted the Jumhuriyah, or Republic, as the most advanced form of government ever known to mankind.

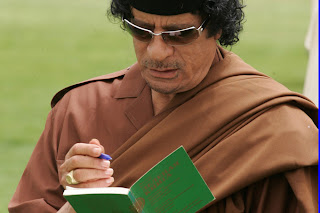

In one volume of his famous Green Book, outlining his solution to the "political problem", he revealed how, through committees everywhere, his new system ended all conventional forms of government – "authoritarian, family, tribal, factional, class, parliamentary, partisan or party coalition" – replacing them with "direct democracy" and "people's power". Society's vanguard, the revolutionary committees, or "those who have been convinced, through the Green Book, of the fraudulence of contemporary democracy", were to incite the masses in their conquest of all bastions of "conventional" authority.

In a second volume, his solution to the "economic problem", he envisaged a society that would banish the profit motive, and ultimately money itself, and where no one would work for anyone else.

The spread of the new gospel was a historic necessity. Just as the European despots ganged together to crush the new republican order to which the French revolution gave birth, so the Arab kings and presidents would round on the Jamahiriyah to preserve their "crumbling power and apostate policies".

But this was to amount to a self-fulfilling prophecy. From being an aspirant for union, President Anwar Sadat's Egypt quickly became a mortal enemy, and waged a vicious border war against its neighbour. Libya came under such assaults not because of the power of a new idea – Burkina Faso was the only other country to declare itself a Jamahiriyah. For in practice, Gaddafi remained a very conventional ruler of a developing country. Behind the pretentious facade, his power rested on a very down-to-earth mixture of totalitarian method and tribal loyalty, with his revolutionary committees as the instrument of policies that came from the top, almost never, as under the "people's power" they should have, from below.

If he achieved anything, it was mainly because of oil – which yielded ever-increasing billions a year for a people of 2 to 3 million – and his freedom to impose his peculiar brand of Arab socialism without regard for true cost. Yet even so, he could not avert the chaos, the grim fiasco of his grandiose supermarkets' empty shelves, of stampedes – in which people were trampled to death – for basic commodities when they did arrive. He also spent huge sums on a Soviet-supplied arsenal. But neither the money nor the 8,000 Soviet technicians could hide the fact that much of it was rotting away in the desert.

No, the foreign desire to stamp out the Jamahiriyah was a self-fulfilling prophecy because, in his pan-Arab frustrations, Gaddafi turned more and more to propaganda, subversion and the patronage of every conceivable "liberation" movement, from semi-respectable Palestinian organisations to outright terrorists such as Carlos the Jackal and Abu Nidal. He openly espoused revolutionary violence, and sent hit teams to assassinate Libyan "stray dogs" who opposed him from exile. In 1984, shots fired from the Libyan embassy in London killed PC Yvonne Fletcher while she was policing a demonstration, and Britain broke off diplomatic ties.

Gaddafi declared war on the American-sponsored peace process and became the US's public enemy number one. In 1981 the Sixth Fleet shot down two Libyan fighters over the Gulf of Sirte in the first military collision, in modern times, between the US and an Arab country. Then, in 1986, President Ronald Reagan sent waves of warplanes to bombard targets in Tripoli and Benghazi. One was the Aziziyah barracks where Gaddafi lived, but instead of the man Reagan called "the mad dog of the Middle East", they apparently – according to state media – killed his adopted daughter, Hanna, instead.

It took some time to appear, but this raid, and above all the attempt to kill him, had a sobering effect. Emulating President Mikhail Gorbachev, in 1988 Gaddafi began a characteristically flamboyant perestroika of his own.

The revisionism was implicit recognition that the Libyan people would have been quite unmoved had Reagan's F-111s got him, that he had reached a nadir of unpopularity, the cumulative consequence of American hostility, foreign misadventures, domestic repression and the havoc wrought by his puerile Green Book socio-economic theories. He mounted a bulldozer and rammed the walls of a well-known Tripoli jail. Political prisoners clambered free from there and other places where they had been incarcerated for years, often without knowing why. Private retail trade trickled back to the long-shuttered Italianate arcades of central Tripoli, bringing with it wonderful things such as soap, razor blades and batteries, which had all but vanished in the era of "supermarket socialism".

The perestroika pleased Libyans so far as it went, yearning as they did for the day when, like any conventional leader, theirs would turn his attention to the ordinary problems of a small and rather ordinary country. It also impressed western diplomats as a possible portent of a radically new Gaddafi, one readying himself to renounce his fierce and flamboyant anti-imperialism and his sponsorship of international terrorism. Yet if, at last, this really did signify the mellowing, on all fronts, of the enfant terrible of the Arab world, it was a process that was suddenly thrown into reverse by a single horrific legacy of the terrorist past which he was apparently trying to put behind him.

That was the bombing, in 1988, of Pan Am flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, with the loss of all 259 passengers and crew aboard, along with 11 people on the ground. After a huge international investigation, in 1991 Britain and America accused Libya of responsibility, and demanded that it hand over the two chief suspects, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and al-Amin Khalifa Fahima, members of Gaddafi's intelligence services, for trial.

His first instinct was to rail and abuse. It would be treason for Libya to do so, it was in a historic confrontation with the west, in the course of which, if need be, it would set fire to all oilfields. Gaddafi was afraid that to yield up those two obscure apparatchiks would be to strike at the very foundations of his tribal-cum-military power. In any case, he had already persuaded himself that it was not just the two suspects that the west was after, but his own head.

On the other hand, if he did not comply, the sanctions, mainly an air embargo,, which the UN imposed in 1992 and ratcheted up a year later, were going to cripple his effort to restore his ravaged economy. He needed, above all, to placate his people, the sanctions' prime victims, who were mostly blaming him, and him alone, for them.

And he was already facing unrest enough. In 1993 he was deeply rattled by a tribally based military rebellion and assassination attempt that he only narrowly escaped. He was also confronting an Islamist terror campaign, in the hilly eastern regions of Libya, partly inspired by those already raging in neighbouring Egypt and Algeria. This put paid to even the pretence of perestroika. It was back to the killing or abduction of "stray dogs" – now conducted with the complicity of his fellow despot, the Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak, a man with whom he was deeply at odds in almost everything else – and back to blood-curdling threats from himself: "When traitors are discovered in a tribe, the Libyan people automatically consider the whole tribe guilty and the people's committees have the right to shoot them dead."

In 1996, one of Gaddafi's brothers-in-law, Abdullah Sannusi, is said to have presided over an alleged massacre in Abu Salim prison, Tripoli, in which guards are said to have gone from cell to cell with Kalashnikovs and grenades, killing 1,200 inmates. And things were apparently getting so bad on the economic front that a law was passed that widened the scope of the death penalty to include "speculation in food, clothes or housing during a state of war".

It was only in 1999, after interminable wrangling over face-saving terms and conditions, that Gaddafi handed over the two suspects for trial in the Netherlands under Scottish law. Two years later, he was outraged at the conviction of al-Megrahi, mocking it as Christian justice and a laughable masquerade. But still this was not enough for the US and Britain. They demanded a clear, official acknowledgment of responsibility for the atrocity and compensation – some $2.7bn of it – for the victims' families. With much squirming, he complied on both counts – and thereby secured the full-scale lifting of sanctions and general rehabilitation he so desperately needed.

It inaugurated what, in effect, was a third great transformation in Gaddafi's international orientation. With the first of them, he had reached a point of such disgust that he pronounced: "Arab nationalism and unity have gone for ever. May God keep the Arabs away from us, for we don't want anything more to do with them." He turned to another continent instead. "Libya," he now decreed, "is an African country." And he expounded his new vision – a United States of Africa, with Sirte as its capital, and himself as its self-anointed king of kings. But before long he was growing tired of Africa in turn, and Africa of him.

Even he could hardly have imagined that he could ever turn Europe into the arena of yet another of his grandiose moral, civilisational and geopolitical designs. Nonetheless, he did treat it to lectures and theories about where its future lay, or should. He already saw signs, he once told it, that God would "grant Islam victory in Europe without swords, guns or conquests" and that "the 50 million [sic] Muslims of Europe would turn it into a Muslim continent with a few decades".

And now, persona grata there himself, he visited on Rome, Paris and other European capitals all those grotesque eccentricities of personal conduct for which he had grown famous, or infamous, elsewhere. His monstrous wardrobe, his entourages of 300 or 400 ferried in four aeroplanes, his huge bedouin tent, complete with accompanying camel, pitched in public parks or in the grounds of five-star hotels – and his bodyguards of gun-toting young women, who, though by no means hiding their charms beneath demure Islamic veils, were all supposedly virgins, and sworn to give their lives for their leader.

Of course Europe was no more going to take him to its bosom than its Arab and African predecessors had. In any case, its main interest, just like his, was business – access to Libya's large reserves of oil, investment and a role in the reconstruction of its economy. And western governments now deemed – somewhat disingenuously – that he was doing enough, in renouncing his former wicked ways, to justify this very pragmatic rapprochement.

And the rapprochement deepened beyond the merely economic. After the terrorist attacks on the US in September 2001, the one-time world leader in the export of terror was gradually elevated into a virtual western ally in the war against it. Then, in 2003, he announced that Libya had decided to get rid of any nuclear, biological or chemical weapons in its possession. President George W Bush and Tony Blair leapt to praise this "courageous and wise decision" – even as they claimed it as a great strategic consequence of their overthrow of Saddam Hussein, and the fear which that had inculcated in other despots.

But these changes, designed to please the west, were not matched by any remotely comparable ones on the home front. Ostensibly, Gaddafi did seek internal reforms of sorts. His second son, Saif al-Islam, had long been openly critical of the Jamahiriyah's deep failings in governance, economic management and human rights. He even led a semi-public inquiry into the massacre at Abu Salim in which it is suggested that his own uncle had participated. It was he whom Gaddafi put in charge of bringing the reforms about.

However, Saif al-Islam did not get very far. For he ran into resistance, not merely from such pillars of the system as its revolutionary committees" and a nomenklatura deeply wedded to the status quo, but also from Gaddafi himself. For, when it came to the crunch, Gaddafi Sr was not ready to let junior do more than tinker with the whole, bizarre edifice of power which he had created, and reminded him that the direct democracy that it embodied was the best in the world.

When it came to the economy, Saif al-Islam could not stray far from the Green Book either. Yes, his father conceded, his economic theory had meant the nationalisation of just about everything. But that, he now said, had been merely transitional. All the theory needed was elaboration and refinement for the benefit of the ordinary mortals who had to make it work, and who, in their obtuseness, opportunism or sheer malevolence, had misinterpreted or abused it.

Gaddafi had come to power as the last revolutionary of the pan-Arab nationalist Nasser generation. He eventually became the doyen of them all. None was to enjoy such absolute power for so long as he, and none had had such an opportunity to shape their systems and societies with quite such untrammelled ease. Consequently, in none had the failure of a whole generation's revolutionary expectations been more blatant than it had been in him.

The "messenger of the desert" reduced his country to a far worse condition than he found it in. Survival, for the 42 years that made him longest-serving non-royal ruler in the world, was about the only thing he could boast of. And till he was challenged both internally and by international forces, there was little to suggest that he could not have survived for many more years, and eventually – like just about every other leader of once-revolutionary Arab republics had already done or planned to do – perpetuate himself and his Jamahariyah in the person of his son. That son would not have been his eldest, Muhammad, from a first, short-lived marriage to Fatiha al-Nuri, but Saif al-Islam, his eldest by his second wife, Safiya Farkash. He is survived by those three and by other children from his second marriage; his sons, Saadi, Mutassim, Hannibal and Khamis; a daughter, Aisha; and Milad Abuztaia, an adopted nephew. His son Saif al-Arab from his second marriage was killed in a Nato air strike.

Gaddafi's powers of survival notwithstanding, once the hurricane of the Arab democratic revolution began to blow, nothing seemed more obvious – or fitting – than that he, cruellest, most capricious and ruinous of Arab dictators, should be among the first three to be swept away. It even looked as though he might go as swiftly as the neighbouring presidents Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali and Mubarak in Tunisia and Egypt.

Within days he had lost control of Benghazi, a traditionally self-willed city, as well as vast swaths of eastern Libya. The contagion spread to the west, where important towns and tribal districts fell to local rebellions. Waves of protesters were in the streets of Tripoli itself. And with panic and confusion taking hold in high places, with long-serving officials and military commanders rushing to defect, his power seemed close to crumbling before this tidal wave of pure, unbridled "people's power".

But that was not to be. Turning tanks, artillery and warplanes on civilians, Gaddafi killed and injured thousands. And then, recovering from the initial shock, he rallied what was left of his loyalist apparatus and launched a systematic, multipronged counter-offensive to reimpose his sway over the capital and retake areas lost in the east. Now, it was no longer, as in days gone by, just occasional plotters and renegades who had betrayed him. It was an entire people, "stray dogs" all, "rats, traitors, hypocrites, drug addicts – and agents of al-Qaida". Now, he and Saif al-Islam vied with one another in warning of the "rivers of blood" to come if this aberrant people failed to make the only sensible choice available to it, between "submission – or liquidation and war until the last man and the last bullet".

As the resurgent military reappeared at the gates of Benghazi – now the rebel headquarters and seat of a rival administration – a massacre loomed. And that prospect triggered a reaction that was probably decisive to Gaddafi's ultimate undoing. With broad Arab backing, Nato forces imposed a no-fly zone over the country. Their mandate was to protect civilians only, but in due course they became a de facto instrument of regime change, in conjunction with the rebel forces on the ground.

Western aircraft steadily eroded the Gaddafi military's ability to exploit its vastly superior, and professionally delivered, firepower, targeting concentrations of artillery and armour as they lay siege to rebel-held cities. Chaotic at first, without training or any but the most rudimentary equipment, and fired only by enthusiasm and reckless courage, the disconnected groups of volunteer fighters gradually acquired sufficient military skills and improved, makeshift weaponry first to hold their own, and then to achieve minor gains here and there.

After six months of stalemate, they surprised the world, and perhaps themselves, with their lightning descent on the capital and their conquest of the Bab al-Aziziya barracks – that vast, forbidding high-walled fortress, home, seat of power, and above all, crass, iconic, absurdist symbol of Gaddafi and all his works. It was only a matter of time before National Transitional Council forces took control of the rest of the country, and even Sirte finally provided no refuge.